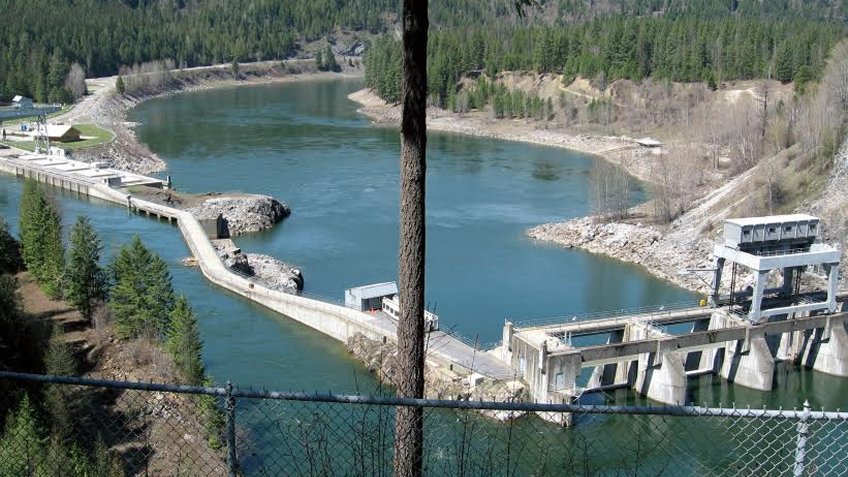

Box Canyon Dam was turning river current into electrical current long before “renewable energy” became an environmental gold standard. Since 1956, the dam and its four hydroelectric generators have straddled a narrow section of Washington State's second-largest river, the Pend Oreille (Pond-er-ray).

The Pend Oreille County Public Utility District built and operates the 80-MW-capacity hydro plant, which today provides renewable energy to 8,500 customers. Box Canyon is a run-of-the-river hydro plant, meaning the flow of water from upstream sources drives the submerged turbines. Control is critical to maintain the delicate balance between optimal power generation and the river's natural ecosystem.

Seasonal rains, melting snowpack and other natural forces put pressure on Box Canyon, swelling the incoming flow from upstream dams and reservoirs. Swift currents are a plus for hydropower production because they turn the turbines efficiently, which then spin electromagnets to generate energy.

However, state-protected lands behind Box Canyon can't be allowed to flood. These lands are home to sensitive animal habitat and picturesque public parks that attract thousands of visitors annually. Because of this, Box Canyon operators work continuously to control the amount of water flowing through the dam and the elevation of the river behind it.

Upgrade Needed

This operational and environmental equilibrium has been achieved largely by hand at Box Canyon Dam because most of the original mechanical controls and hydroelectric equipment — including the four turbines, generators and auxiliary machinery — remained in use more than 50 years after they were installed.

“Even for a team of highly experienced operators, that's a lot of working parts to monitor and adjust separately,” says Terry Borden, manager of hydro production at Box Canyon. “We also have to contend with whatever the weather throws at us.”

While the average flow rate at Box Canyon is 26,400 cubic feet per second (cfs), spring thaws and early summer rains can push that level to 80,000 cfs and above. At those rare heights, operators stop the turbines and open the dam's hydraulic gates to let the rushing river flow unfettered through spillways.

Day-to-day fluctuations in the river are far less dramatic, but still can vary significantly. To contend with those variations, operators consistently monitor flow rates and water elevations behind the dam. They use that information to control the flow through the dam by adjusting the turbines' wicket gates, or large doors that open to allow water into the turbines. The goal is to keep power production as close to peak as possible while keeping river levels as stable as possible.

Collecting the critical data involved in the power generation process has been a largely manual process, with operators recording instrument readings by hand. Without an electronic network to share the data, operators had to enter it into Excel spreadsheets, and then distribute hard copies to other departments. Purchasing employees, for example, use month-to-month trending data to help calculate power contracts.

![PlantPAx process automation solution includes two Allen-Bradley ControlLogix programmable automation controllers for each turbine/generator unit at Box Canyon Dam in the state of Washington. [Click to Enlarge]](https://rockwellautomation.scene7.com/is/image/rockwellautomationstage/box-canyon-3-hires--graphic-280w.280.jpg)